In this final part of a four-part series, Danny Casey looks at the life and career, for the most part controversial and contentious, of arguably the greatest tunnel-boat builder and driver of all time. An enigma, a doyen of intimidation and a master of psyching out the opposition but, above all, an immensely brave, supremely fast and inordinately talented practitioner of race-craft. Had this man participated in any other sphere of motorsport, he would still be revered, venerated and feted as a hero today, able to command regular appearance fees as an all-time legend at retro race events, but instead he virtually disappeared from view, maybe even becoming somewhat reclusive, once the halcyon era of circuit racing had reached its peak and fizzled out. If there were ever a Nuvolari, Ascari or Farina of the powerboat world, it would be this man – a man who won almost everything in every single class of boat in which he competed, and always against top-rank peers who were also at the peak of their powers.

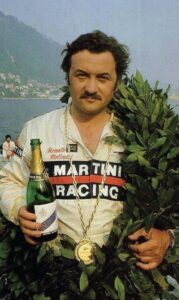

In a recent idle moment, I was browsing through some online historic boat-racing sites when I chanced upon a picture of an oldish man – not tall or particularly well-built – perched a little awkwardly, almost incongruously and self-consciously, on the sponson of a modern-day race boat from the F1H20 World Championship Series. The man looks like someone’s grandpa, where a kid had maybe spontaneously chirped: “Here, Grandad; sit on this boat and I’ll take your picture.”

The man couldn’t be anything other than Latin – Italianate, if one were to surmise correctly – and he has an impish but reticent and cunning smile.

His face is lined and weathered yet proud, and has retired craftsman (carpenter, stonemason, or maybe even plasterer or house-painter) written all over it. He is dressed in unflattering and utilitarian pants – not well-cut Chinos but functional trousers solely for the purpose of covering one’s legs. The pants are scuffed behind the man’s left knee. On the man’s feet are a pair of trainers – not chic, name-brand or high-tech trainers, but trainers constructed purely to keep a weatherproof membrane between the wearer’s feet and the elements.

He has also been given – maybe at the last minute – a jacket emblazoned with the name of the powerboat racing team. The jacket is a tad large, with a sleeve stopping just short of his knuckles. There are no allusions to greatness and prosperity – either present or past – but one somehow knows that this man has seen and done much in his lifetime and is now winding down in his twilight years. He certainly has done and achieved much, and he has more than a passing familiarity with the type of boat on which he is now seated.

The man has in fact been the European and World Powerboat Champion many times in every major class of racing – in fact, eighteen times in total (on top of multiple Italian championships), and always in boats designed and crafted in his own factory and bearing his family name. The oldish man in that photograph is called Renato Molinari.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the halcyon days of circuit powerboat racing and the era of the factory wars between the two major US outboard companies, Mercury and OMC, there were the Americans and the Europeans. At that time, the US had drivers like Bill Sirois, Jimbo McConnell, Bob Hering, Tommy Posey and Mike Downard, while Europe had the likes of Bill Shakespeare, Bob Spalding, Tom Percival, Jackie Wilson and a fast, tidy and very stylish Italian driver by the name of Cesare Scotti.

The Americans raced whatever boats they were given, but two of the Europeans – Shakespeare and Scotti – built their own.

Cesare Scotti was, before his untimely and gruesome death at Paris in 1974 (in a boat of his own design which was never intended to carry the V6 Evinrude that had been installed on it for that race), the classic stereotype of the Italian race ace – charismatic, good looking, personable, very fast and inordinately brave. Scotti was the cousin of an up-andcoming youngster, whose family also manufactured boats – for both pleasure and competition – in the same area, which was Lake Como. Scotti’s young cousin was Renato Molinari. In later years, Molinari – not known to willingly or graciously heap praise any of his opponents – never ceased to eulogise his cousin Cesare and laud him unquestionably as the best of the very best.

To say that boats were in the blood of Angelo Molinari and his sons Renato, Giorgio and Franco would be like saying that Enzo Ferrari was a garagiste – they literally lived above a waterside factory and were on the water every single day. Furthermore, Renato Molinari’s first job away from his family’s enterprise was as a test driver, aged 18, for the Glastron Boat Company in Texas, and as that time – the mid-1960s – was a seminal era for advances in outboard-powered boats (with trials of early catamaran designs and experimentation with power-trim systems), there is little doubt that the young Molinari would have returned to Como with knowledge that many men twice his age would take several years to amass.

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, The Six Hours of Paris was the world’s flagship powerboat racing event, with the race having only a temporary respite from commercial traffic until the workboats and barges were again allowed through the middle of the circuit on the Seine from noon onward – so the water conditions for the final two hours bore no relation to the conditions during the four hours that had preceded them. There are some drivers indelibly associated with a particular circuit (like, for example, sportscar legend Jacky Ickx at Le Mans), and such was the case with Molinari at Paris – which he won four times.

Once, before the flag dropped for the start of one of his most (in) famous victories (in which he was ostensibly a privateer despite being allocated a Mercury Twister by the factory), he and his brothers had repeatedly asked the Mercury team manager, Gary Garbrecht, if the motor on Molinari’s boat was built to exactly the same spec as the factory drivers’ units. The question was repeated ad infinitum until a beleaguered and infuriated Garbrecht assured them most emphatically that, yes, their engine was exactly the same as the factory units. “Ah, issa good for you,” replied Molinari, “because we climbed over the fence into the boat park during the night and swapped the powerheads!”

Like all great sportspeople and true champions, there was an inscrutability and mystique to Molinari – an unsociability, almost. He seldom fraternised with his fellow drivers, except maybe when selling them boats (which, invariably, were never quite as good as the version he kept for himself). Even the late Charlie Sheppard, the renowned English builder of the renowned Bristol-marque monohull circuit boats and the man behind the famous Grand Prix in the city’s docks, found Molinari hard to read. One afternoon before the running of a race in the early years of Bristol, Sheppard was confronted by a hire car screeching to a stop right outside the docks, out of which spilled Molinari, his brother, Giorgio, and at least two more Italians. “Where is the circuit?” Molinari brusquely asked, thinking that the narrow sliver of water before him was only one side of the circuit, and that it was maybe divided by a wall or island in the middle, much like the circuit on the Seine was divided by the Ile aux Cynges. Charlie Sheppard answered, “Well, you drive up that side keeping to the right, turn around the buoy and then come down this side, also keeping to the right”. To which Molinari, seeing the course for the first time and showing no sign of trepidation or discernible concern, indicated he understood with a simple: “OK. Issa maybe a leetle tight but we race.”

Other great drivers like, for example, the superb multiple World Champion (in both F3 and F1), Welshman Roger Jenkin (who sadly passed away in late 2021), maintained that while Molinari may have been a doyen of the sport, he was anything but a good sport. Other observers maintained he could also be intimidatory and threatening, and would have no hesitation in scrambling over a row of boats lined up for a dead engine start to jump onto some particular driver’s foredeck, then lift that driver’s visor and scream at him to keep clear of him. All drivers agreed that nobody could make a boat appear as “wide” as Molinari – he was extremely, if not dangerously, difficult to pass. But, for all that, he was undoubtedly an artisan.

Where many of the drivers of his era were every bit as skilful, committed, fast and brave, some always seemed to be a bit more frenzied, ragged, and on the edge when chasing, or being chased by, Molinari. The late, great Tom Percival (tragically killed at Liege in 1984), for instance, used to lean ever further forward, helmet almost seemingly touching the wheel, when he was on a charge, but Molinari – despite a fiery and doubtlessly highly-strung Latin temperament – always sat well back, arms outstretched in the classic competition-driver’s pose (like Ascari or Fangio), with his head nestled into the back of the cockpit. Even when his boat danced, jittered and skittered on severely chopped-up water, he never let too much air blow through the tunnel and always kept the bow relatively low.

Some observers have also remarked that Molinari just didn’t get into a boat and accelerate away – there always appeared to be a period of introspective reflection where he seemed to be psyching himself. In fact, I can think of at least three images over the years: one where Molinari is standing in a cockpit, head bowed and hands crossed at his waist; another similar image in the same position with him holding his helmet and staring into the distance, then another of him on Lake Como kneeling on the sponson and staring ahead in a state of deep concentration. In all these images, it looks as if he is drawing on inner reserves and getting himself “into the zone”. But although Molinari was on the water every day, he didn’t spend long periods of time testing a boat over and over again – generally 10-15 minutes on the water would suffice and he would then come in to ponder, analyse and improve.

While Molinari had at one time been a member of Mercury’s famous Black Angels Team (with men like Bill Seebold, Earl Bentz, Reggie Fountain and Cees Van der Velden), he never really came into his own and garnered his mythical, enigmatic image until he was signed by Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) in 1977. By late 1976, OMC (manufacturer of Evinrude and Johnson outboards) was beginning to realise that, in Europe, the Japanese manufacturers were no flash in the pan; that they were there to stay, and taking chunks out of OMC’s European market share to boot. OMC believed that a key way to attack and beat the Japanese would be to realign pricing and, to this end, they took the momentous decision to cut ties with nearly all of their independent European distributors (many of whom had represented OMC products for decades), thereby presumably eliminating one whole tier of mark-up margin. They then opened their own direct factory affiliates in key European markets – the only exceptions being the distributor in Spain and the huge, long-standing Evinrude importer in Italy, Italmarine. As part of the new, rejuvenated image, OMC decided that competition would form a huge part of this mammoth repositioning of their products – so, to this end, Molinari was signed as their de facto factory racing entity.

Unlike automotive racing, it is highly unlikely that any powerboat racer has ever become rich while driving for a factory team, but the vast amounts of money, resources and equipment OMC threw at Molinari from the mid-late 1970s to the mid-1980s defy comprehension. These were his golden days and his renaissance era, and there seems little doubt that he had financial security and resources which were to dissipate greatly once his factory involvement finished. In terms of machinery, one would really have to be a hopelessly tragic pedant to keep track of all the specialised, one-off race motors allocated to Molinari. There are pictures of his iconic Saffa Lighters Team race boats in the late ‘70s, where a teammate, the American ace Bob Hering, was running a carburetted V6 2,448 cc crossflow Johnson with more or less the standard, bulky, leisure-spec engine cover, but Molinari’s Evinrude engine had a completely different, slightly sleeker profile, with a lower, pancaked top to the engine cover – it turned out that Molinari was running a special 3-litre loop scavenged engine (never, ever released and different from the subsequent 3-litre loopers of the 1980s) with fuel injection. In relation to supposed “teammates”, they were just other drivers that Molinari needed and wanted to beat – the fact that they were supposedly racing under the same umbrella was neither here nor there. Nor was he averse to politics.

One of his most ignominious acts was at Bristol in 1977, where he (as distinct from the engine manufacturer, OMC) had hired Bob Hering to drive the second of the two Saffa Lighters Team OZ class (unlimited) race boats. Racing was over two days – Saturday and Sunday – with two races each day. Molinari won three of the races in succession and had accumulated so many points that he elected not to run in the final race on Sunday. Hering, however, had other ideas. He had finished 2nd behind Molinari in all three races and he believed that, with Molinari out of the picture in the last heat, he could win it – he tallied the potential points in his head and reckoned that if he won, and with Molinari not even starting, he could theoretically beat Molinari. And Hering had indeed settled himself in the cockpit for the last heat only to be physically manhandled and yanked out of the boat by members of Molinari’s crew. Of course, had poor Hering been an OMC driver as distinct from Molinari’s paid second fiddle, then brutal politics of this type might never have been allowed to play out.

Then there were the theatrics, the psyching-out of competitors and the mind games – boats being launched or recovered with their sponsons hidden by tarpaulins so nobody else could see the water-contact surfaces of the boat. There was probably little, or anything, markedly different about the running surfaces of these boats, but it was all a matter of sowing doubt and consternation in competitors’ minds. One time Molinari actually did have a tarpaulin-shrouded “secret weapon” on his boat was when he had fitted an “air brake” system to the OZ Evinrude-powered Saffa boat at Chasewater, UK, in 1978. He applied the brake for the turn in front of the grandstand and the boat literally disintegrated into detritus – Molinari luckily sustaining damage only to his pride.

Towards the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s, Molinari seemed to be becoming more pragmatic, philosophical and wary, as he was regularly encountering aggressive, close quarter competition from the likes of probably the greatest race-boat driver ever, the American, Bill Seebold, and probably the world’s best rough-water driver, Cees Van der Velden from Holland. And he was possibly acutely conscious of the high risk of mortality, too. This was the insane era of powerboat racing just before safety cells on race boats started to appear, where the top boats powered by the OMC V8 “King Kong” motors were running at close to 140 MPH with the drivers wholly unprotected – undoubtedly the most dangerous era in any motorised sport. There was talk, around 1983- 1984, that he had lost his edge and would – or could – no longer drive at “ten tenths” every single time, but the fact is that he had seen the deaths of some top-flight drivers like Peter Inward, Luigi Valdano, Gerard Barthelemy and Tom Percival and he probably realised that somewhere, someday, he would be called upon to settle the account for the life he had chosen.

Much was made of the fact that the hard-charging, “win-orcrash” American driver, Barry Woods, beat him in several races during the 1984 season, but the truth is that once Molinari had amassed the points necessary to secure what was to be his final World Championship, he realised there was no point in hanging on the ragged edge for longer than was necessary.

This writer had intended to finish this profile with a “what is he doing now?”-type of epilogue, but Molinari, other than popping up occasionally at boat races in Europe, keeps a very low profile. The magnificent on-water facility on Lake Como, previously housing both the Molinari family residence and the boat shop, is now an apartment block called “Casa Molinari” (in which one can apparently book a stay through Airbnb). There are myriad reasons for this, but it has been reliably posited that the Italian taxman had much to do with Molinari’s departure and downfall and, in general, he has been enduring somewhat straitened circumstances since he quit racing. Whilst he never had many (if any) friends in his racing days, he undoubtedly had many begrudging admirers, and it is sad to see a legend of any sport disappearing into semi-obscurity like this. If one thinks of any branch of motorsport, one would be hard pressed to name anyone who was so committed, so professional, so successful, so fast and so blessed with luck – for so long. Molinari wasn’t just a part of boat racing; he was boat racing, and he and his fellow gladiators are now mere memories in the fast-fading minds of those of us lucky enough to have seen them at the pinnacle of their powers and in their prime.

Danny Casey is highly experienced, undoubtedly idiosyncratic, and immensely knowledgeable about things mechanical, new or old. His knowledge and passion are as a result of spending his whole life in or around anything power-driven – especially marine engines. His passion for boating is second to none, with his life a montage of fabulous memories from decades spent in or around water and boats, both here and in Europe. Danny has spent myriad years in the recreational marine industry in a varied career in which he has bamboozled colleagues and competitors alike with his well-honed insight.

His mellifluous Irish accent, however, has at times been known to become somewhat less intelligible in occasional attempts at deliberate vagueness or when trying to prevent others from proffering a counter-argument or even getting a word in. Frank and to-the-point, but with a heart of gold, it can be hard to convince Danny to put pen to paper to share his knowledge, but Marine Business News is grateful that he took the time to share this, the fourth and last part of this special series. Connect with Danny through LinkedIn.