In this, the third part of our four-part series, Danny Casey examines the life, times and shocking, brutal death of the man who put the gloss, glitz and glamour into the then gritty but nascent sport of offshore powerboat racing – a man whose creation of an all-onquering, epoch-making race boat resulted in the adoption of a generic name for all boats of that type thereafter. The boat was known as “The Cigarette” and the man behind it created a legacy, an empire and maybe even a mystique that still resonates today.

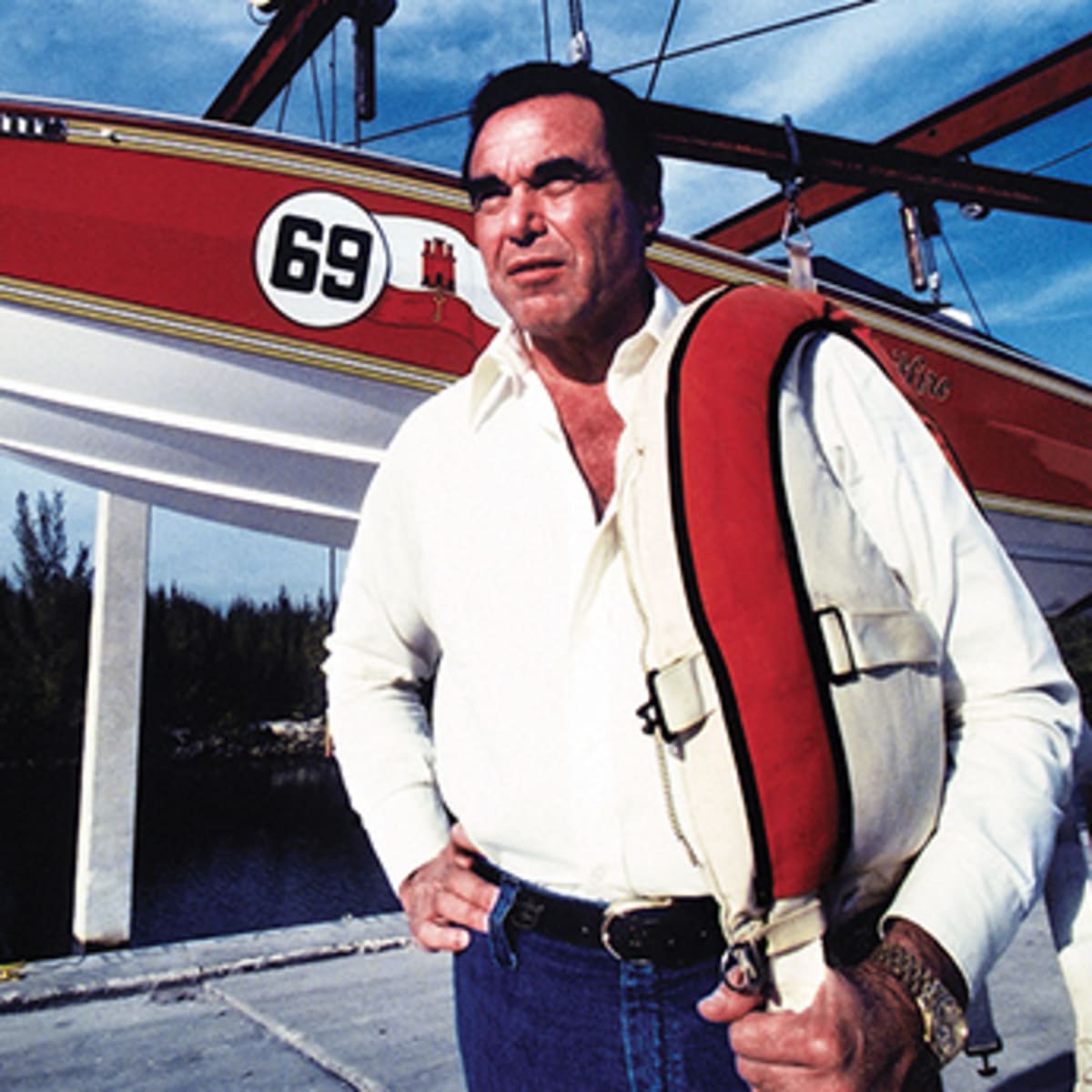

Northeast 188th Street, North Miami was a bland, seedy industrial area, made up of nondescript boatbuilding facilities and allied fabrication and engineering businesses. It was the sort of stark industrial area one would also find in Auckland, Sydney, or Los Angeles. However, NE 188th Street also had an imposing and impressive alternative name that belied its stark environs. It was, and still is, known as Thunderboat Row and was so named because it housed, along both sides of its short length, several companies involved in the building of high-performance offshore powerboats. And nearly all these enterprises were spinoffs of the original company started in 1963, in that very street, by Donald Joel Aronow.

In the drug-fuelled, hedonistic Miami of the mid-late 1980s, the only excitement in this otherwise nondescript street was when the magnificent creations from these factories, were craned into the canals that flanked the dead-end road for testing. But other than the start-up barks of powerful engines that then idled and lolled out into open water, the street went about its regular business of constructing very fast boats in purpose-built facilities.

On Tuesday, February 3rd, 1987, an otherwise unremarkable Miami winter day, a man walked unannounced into the office of Don Aronow’s newest boat company, USA Racing Team, on the

premise that he was there on behalf of his boss, who was extremely wealthy and could not therefore be identified.

This representative for the mystery buyer was muscular, well-built and very tall, at maybe six feet four inches. He looked sturdier, fitter and heavier than Aronow, who was himself six feet three and 220-plus pounds (in US parlance).

The visitor said his boss wanted him to talk to Aronow about purchasing a custom-built boat. Aronow said that that would be no problem; he’d gladly take the guy’s boss’s money and build whatever the boss wanted, but it’d be better if he talked with the boss directly. As the conversation progressed and it became apparent that the name of the visitor’s mystery employer would not be forthcoming, Aronow asked the visitor for ID and the guy made a great flourish of reaching round to his rear pocket for his wallet. “Whaddyaknow,” he said. “Musta left it in the car.”

Aronow then asked him his name, and the guy answered: “Jerry Jacoby.” Aronow knew Jerry Jacoby well, as Jacoby had been the 1981 UIM World Offshore Champion and the 1982 US Offshore Champion – but this visitor was not Jerry Jacoby.

Aronow, who had seemed preoccupied and edgy for weeks, rushed to leave and fobbed “Jacoby” off on his sales manager, telling the sales manager to take the visitor out to the yard to show him the boats. But the guy had no interest in seeing any boats and briskly exited the premises.

Some minutes later, seemingly rattled and distracted, Aronow left the office, got into his white Mercedes-Benz 560 SL convertible and drove the short distance up the street to see a friend, Bob Saccenti, who was also a business competitor, at Saccenti’s boatbuilding company, Apache Performance.

Saccenti had been injured in a recent powerboat race and Aronow wanted to see how he was doing. After some minutes schmoozing and trading friendly – albeit rather forced – banter and jibes, Aronow got back into the Benz to return to his own factory. As Aronow pulled out of Apache Performance and turned right to return to USA Racing Team, a Lincoln Town Car approached from the opposite direction. The Lincoln (some said it was black while others swore powder blue) slowed and the driver’s window glided down. An arm discreetly signalled Aronow to stop, so he drew alongside the Lincoln and braked – both drivers’ windows side-by-side. A very brief conversation, measured in seconds, ensued, and the driver of the Lincoln extended his arm, in which there was a serious firearm: a semiautomatic .45 calibre Colt. Six shots were fired at Aronow, five of which hit him (one in the groin), with the sixth tearing its way through the passenger door.

Eyewitnesses say the Lincoln pulled away, smoothly and purposefully, but not overly rapidly, and then drove over a patch of waste ground before escaping through a warren of back streets with not a single traffic light before the freeway.

Aronow was slumped in the car with the engine screaming madly, his foot jammed hard on the accelerator and the transmission in neutral. This was strange but, as his wife later posited, would have been because of his background with boats.

Whenever he came to a halt in his car, he always slid the automatic transmission lever from “D” to “N” – just as one would do when idling a boat. His wife maintained that if he hadn’t adopted this peculiar, boat-inspired, shift-into-neutral practice, he would have been able to get away rapidly and cheat death – but, as will become clear, that would only have postponed his demise. So badly ripped apart was Aronow’s body that paramedics at the scene said that the fluid from the IV drips was running straight out through the wounds and onto the street.

Leaving aside, for the present, his gruesome end, Aronow, up until then, had lived a charmed, healthy and wealthy life. He was in the vanguard of the “snow birds” from New York and New Jersey (Aronow was from Brooklyn, NY) who migrated to Miami in the early ‘60s, just as the town was beginning to recover from straitened times in the late ‘50s. The Mob (i.e. the Mafia) had had great plans for Miami, as it was the nearest US city to Batista’s Cuba – Batista, of course, being the dictator who allowed the Mafia to build and run casinos in Havana while palming his share. But then Castro deposed him and that was the end of the Mob’s Vegas of the South.

Aronow had done well in the construction industry in New Jersey in the 1950s. In one of his early deals as a young man, he bought a tatty parcel of land on which he built 10 small “starter” houses. Each house sold for $14,500 and Aronow made a profit of $4,500 per house. Not vast sums of money even then, but it showed an eye for a buck and the ability to make a quick killing before moving on to another deal. However, in the north-eastern states at that time, anybody with any knowledge of the construction industry would have known that there was great power held and wielded by the labour unions, and if one wanted to get ahead, one had to know how to deal with the unions. And backing the unions was another altogether more menacing, dangerous entity: the Mob

Aronow was barely in his mid-thirties when he decided to decamp to Miami in semiretirement, and he began to hang out with a powerboating crowd – people like Dick Bertram, Sam Griffith and Dick Genth. He developed an initially mild interest in offshore powerboat racing, participating with moderate success in boats he had bought.

Eventually the bug bit and he hooked up with two legendary boatbuilders, Jim Wynne and Walt Walters. Land was cheap in Miami at the time and, in 1963, he built a boat plant on a scrubby piece of waste ground at NE 188TH Street. He called the company Formula Marine.

This marked the birth of one of the most successful, venerable and much-copied V-hull powerboats of all time. This boat, the Formula 233, designed by Wynne and made production-ready by Walters (it’s debatable if Aronow himself ever had much creative or design output into any of his boats), became a soaring success in terms of both sales and competition, and Aronow appointed a dealer network but gave them paltry margins so they couldn’t discount the boat – thereby keeping both residuals and brand recognition high.

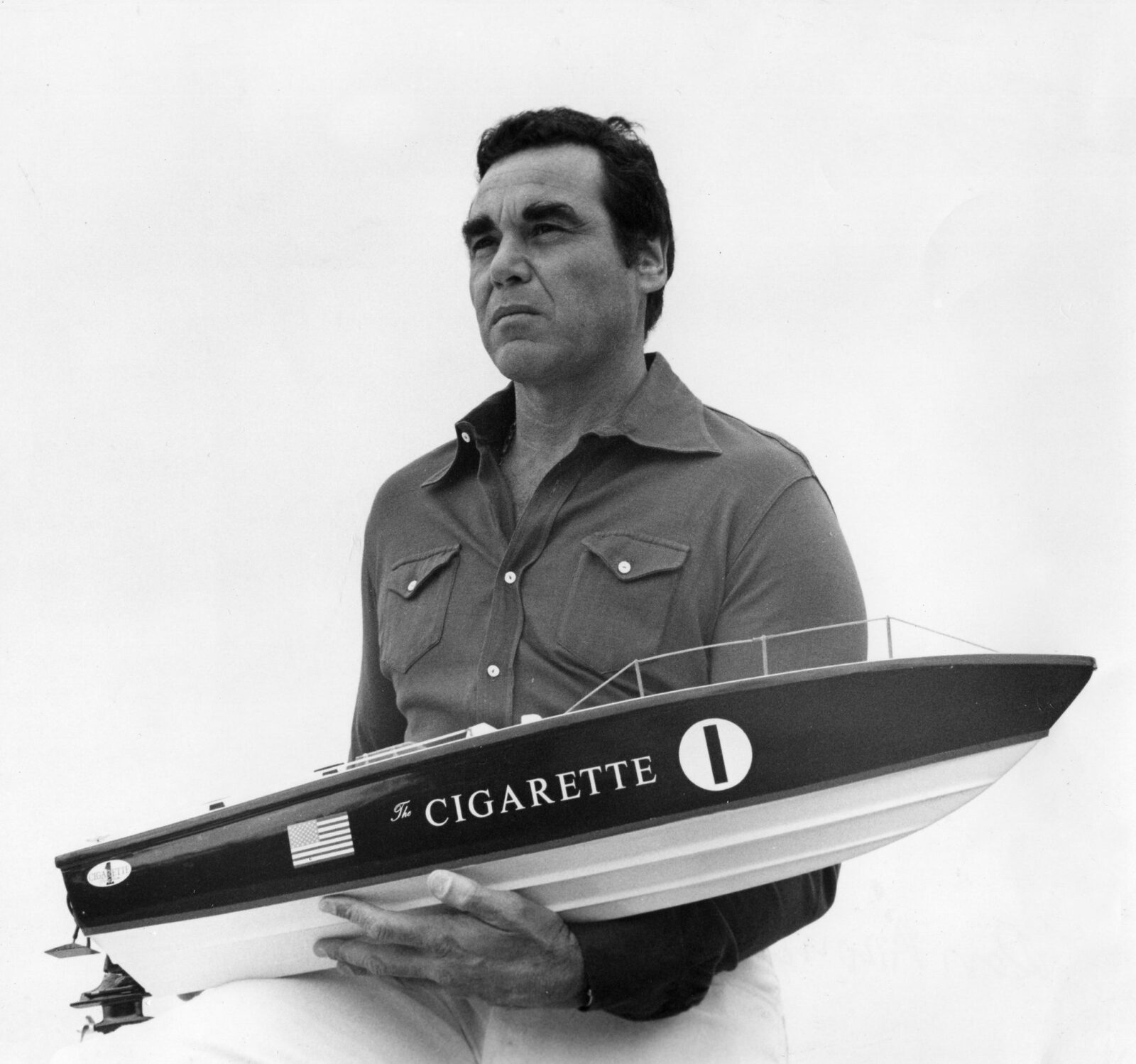

Aronow realised that whilst there was a living to be made building boats, the real money came from pumping up the product and its brand equity and then selling the company. And this is what he did with Formula after only one year – he sold it to Thunderbird. With the deal done, he bought another parcel of tatty land on NE 188TH Street, and started his second company, Donzi – another boat brand with a racy and exotic name. By 1966, Donzi had been sold to Teleflex and Aronow went on to buy a further block of land on the Row and start yet another boat company, Magnum.

Magnum was then sold in 1968, to Apeco, but Aronow now found himself, for the first time, having to rigidly adhere to a strict non-compete clause which had been imposed by Apeco. To circumvent this condition, Aronow appropriated the name of a willing friend, Elton Cary, and built a new range of boats under the Cary name. This was when the legendary “Cigarette” branding first appeared, as the first two models, the 28 and 32, were named after a famous rum runner’s launch of that name from the Prohibition era.

After Cary/Cigarette, there was Squadron Marine and then, finally, USA Racing Team – and each of these moves involved selling the previous company and buying yet more land on the Row to start another one. Aronow could be hard, combative and mean, as the buyer of one of his previous entities discovered. The buyer was loading a boat in the yard with a forklift one day, when Aronow and a bailiff arrived to repossess the machine. “You can’t do this.” The new owner protested. “I bought this company and all its assets, lock, stock and barrel.” Aronow thrust the original inventory list in the guy’s face and said, “But not the forklift – it’s not listed on this sheet.” And he was right. Every piece of plant and equipment was listed – except the forklift (worth maybe a paltry five or six thousand dollars). This indicates a mercenary and unsavoury side to Aronow’s character.

By the early 1980s, the words “Miami” and “narcotics” were intertwined and synonymous, and the TV show Miami Vice explored this fraught symbiosis in every episode. Everyone knew that the days of tramp steamers and fishing boats being used to transport, and land drugs were over, and that go-fast boats were being used instead. In fact, the entire Miamicentric world of offshore powerboat always had the taint of drug money hanging over it, and when such superstar drivers as Joey Ippolito and George Morales were arrested and jailed for long stretches, that confirmed the speculation.

It is highly unlikely that Aronow was oblivious to the machinations of the offshore racing scene, as much of his product ended up in the hands of those who ferried narcotics and those legal entities who attempted to apprehend them.

By now, Aronow was operating his latest and – although he didn’t know it – final venture, USA Racing Team, which he ostensibly ran alongside a powerboat racer and high school dropout (and, by all accounts, a borderline moron) named Ben Kramer. But it was complicated, as Aronow had supposedly sold USA Team Racing to Kramer (with a sizeable sum of money reputedly passed under the table by Kramer to Aronow), so Aronow was merely the company figurehead. This was a futile attempt to bestow some respect on Kramer, who was a major league drug smuggler and who was wholly unfit to operate a legitimate enterprise.

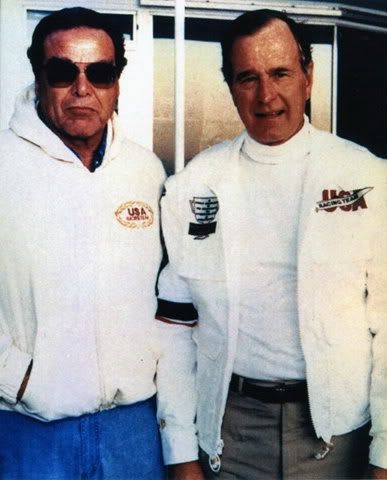

A further complication came in the form of the then vice president of the United States, George H.W. Bush. A personal friend of Aronow, he had always owned Cigarette boats. Whilst Bush was a mainly insipid vice president, Ronald Reagan had appointed him as his personal drugs tsar and it was Aronow to whom Bush turned for assistance with the purchase of high-speed interdiction craft that could chase down the drug runners’ boats. Notwithstanding the fact that Bush and Aronow were friendly, a personal entreaty of this nature was most strange in relation to a high-value government contract, as such purchases are always made at a national level through an official tender process. However, Bush, after a visit to Miami and a day schmoozing on the water with Aronow, tacitly awarded Aronow the contract. But there were two problems.

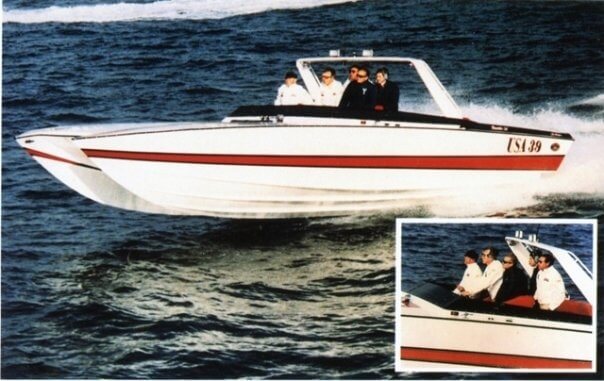

The first problem was that the tunnel-hulled boat Aronow cobbled up for US Customs – the first of what Bush called the “Blue Thunders” – was a total aberration. It was a monohull cut along the length of the keel and “peeled” open. The open side of each of the two (now extremely narrow) hulls was glassed in and both hulls were pushed slightly apart so that a deck could be added. This was supposedly a catamaran but the final product was the enlarged equivalent of two sideby-side kayaks with a pantry door strapped lengthwise over them. Consequently, the tunnel was so narrow that there was no aerodynamic lift and the running surfaces of the hulls were so knife-edge narrow that the boat had no hydrodynamic lift either.

This boat, when fitted with two 440 hp MerCruisers and fast but fragile TRS drives, could manage no more than 56 MPH – compared with drug-running boats that cruised in the high- 70s. In fact, the engines had to work so hard to plane and push the boat, and the TRS legs had to withstand so much strain and heat from trying to keep a boat with virtually no flat surface area on the plane, that failures of both items were measured in weeks, not months.

The second problem, however, was much more serious: Ben Kramer. Bush eventually found out that Kramer, a drug baron, was the true owner of USA Racing Team, and yet here he was on the verge of being awarded a contract for drug interception vessels – a sick and ironic joke!

Bush then contacted Aronow, unequivocally telling him that the deal was off unless, or until, Aronow bought Kramer out of the company and took back control. Aronow ostensibly did this, but whether in fact it ever actually happened is still a matter of conjecture today. But regardless of Aronow’s putative repurchasing of the company, he almost certainly never gave Kramer back the reputed under-the-table sum from the initial sale.

The boat company improprieties, bad as they were, were not insurmountable for Aronow – while his reputation and standing with Bush, for one, would have been tarnished, he would have lived to fight another day with myriad other deals. Where Aronow’s life gets murky (and there have been countless books, articles and theses written about it, all of which are plausible but all of which are nonetheless conjecture) is in his dealings with union – and by default Mob – activists, firstly in New Jersey and later in Miami. It is no secret that Aronow was acquainted with the venerable Mob boss, Meyer Lansky, and it is highly likely that, with all the drugs and drug money sluicing through Miami in the late ‘70s to early ‘80s, large sums of that money would have been laundered through Aronow’s businesses – whether for legitimate purchases or not.

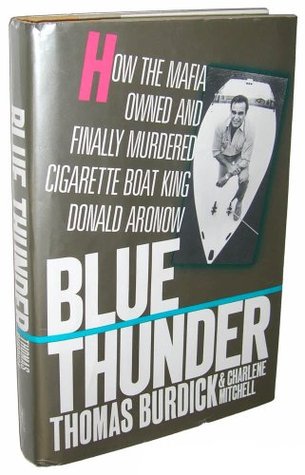

Two journalists, Thomas Burdick and Charlene Mitchell, wrote the superb opus, Blue Thunder, a magnificent chronicle of almost 400 pages on Aronow’s life and death (boat talk is a relatively minor part of the book), and it is probably the definitive reference work on this subject.

Throughout the book, the Mob are never far from centre stage and reliable reports of dons, capos and “wise guys” litter almost half the page count. This book states that the Justice Department had prepared a subpoena for Aronow on February 2nd, 1987, in relation to organised crime, and that it was due to be served on him one day later, on February 3rd, the day of the murder.

No one can say with certainty what really happened but, allegedly, someone in the Justice Department, with a connection to the Mafia, saw the subpoena on an adjacent desk and called the Mob. Aronow was going to be asked about a lot of deals and associates, and although he could have “taken the Fifth”, his silence would have been a tacit admission of complicity. So the Mob scrambled a hit team at the last minute – the wellbuilt guy who entered Aronow’s office on the pretence of boat-shopping for his rich boss (and whose job it was to destabilise Aronow), plus the shooter who drove the Lincoln.

A no-account loser and career criminal named Bobby Young eventually pleaded no contest to the manslaughter of Aronow, saying that he acted on behalf of Ben Kramer, who was angry about having to return the business to Aronow and about Aronow retaining the original under-the-table money. Young had nothing to lose, as his plea on the Aronow matter would see him removed to a less harsh prison, and the sentence for Aronow’s manslaughter was concurrent, anyway, so he wouldn’t have to serve any more time. Kramer admitted nothing, but was in prison for life anyway, with no possibility of parole (where he remains, apparently, to this day).

However, it is pretty much accepted that neither man was associated – at least directly – with the murder of Aronow. Young in no way resembles the wellbuilt guy (whose name is known) who appeared out of the blue in Aronow’s office, and neither he nor Kramer matches the description of the driver of the Lincoln (whose name is also known).

The man from Aronow’s office is the biggest mystery of all – he went in, supposedly to flush out and destabilise Aronow, but fled and disappeared. And according to eyewitnesses, there was only one person – the shooter – in the Lincoln when Aronow was murdered, yet there were two people in it – the shooter and the big guy from Aronow’s office – when they foolishly stopped to seek directions earlier that day. What happened and why, and who really ordered and carried out the hit, and for what reason, was never, ever known – except to those involved.

As for Aronow’s boatbuilding legacy, he built (but probably had little input in designing) boats that were of, and for, their time. He created waterborne glitz, image and braggadocio and bestowed exciting and hubris-filled names on boats that were otherwise pretty mediocre in most key aspects – long, narrowbeamed, pared-to-the-bone, steepdeadrise hulls with no flattening-off aft to assist lift or maintain plane at lower speeds. His boats were power-hungry and brutal, and were fast purely due to the gargantuan horsepower installed rather than through any innovation or creativity in the rudimentary principles of hydrodynamic design.

And as for his legacy as a human being… probably a good guy to encounter for a back-slap and a faux insult in a boat club bar or for a photo-op at a boat race or on a boat show stand, but he straddled two entirely different worlds.

There was a dark undercurrent that would have subsumed those unwise enough to get too close. The legacy and myth are much more appealing than the man.

Danny Casey is highly experienced, undoubtedly idiosyncratic, and immensely knowledgeable about things mechanical, new or old. His knowledge and passion are as a result of spending his whole life in or around anything power-driven – especially marine engines. His passion for boating is second to none, with his life a montage of fabulous memories from decades spent in or around water and boats, both here and in Europe. Danny has spent myriad years in the recreational marine industry in a varied career in which he has bamboozled colleagues and competitors alike with his well-honed insight.

His mellifluous Irish accent, however, has at times been known to become somewhat less intelligible in occasional attempts at deliberate vagueness or when trying to prevent others from proffering a counter-argument or even getting a word in. Frank and to-the-point, but with a heart of gold, it can be hard to convince Danny to put pen to paper to share his knowledge, but Marine Business News is grateful that he took the time to share this, the third part of a special series. Connect with Danny through LinkedIn.