Combating plastic pollution in our seas and oceans is one of today’s most pressing challenges. The environmental organisation One Earth – One Ocean has taken up this challenge and developed Circular Explorer. The Torqeedo-powered solar-electric boat is now cleaning up Manila Bay.

When people gather for a ship’s christening in the Port of Hamburg, it’s usually for a giant cruise liner or mega-containership at a ceremony complete with fireworks and snack stands. But on this misty summer’s day, the vessel tied up to the quay is just 12 meters long and 8 meters wide. At first glance, you can’t even be sure if it’s a boat or a floating dock. And on this day, there’s no supporting program, just a few waiters carrying canapé pyramids and sparkling wine glasses across the quay. Still, you can see nothing but happy faces, camera operators, mikes held up high and journalists ready to take notes.

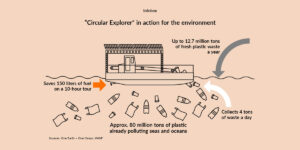

The unique mission of this unusual vessel is what drew attention: freeing seas and oceans from plastic waste. Initially, it seems like a mad scheme given the 86 million tonnes of plastic waste WWF estimates are already in the sea, with almost 13 million tonnes added each year. Yet this vessel demonstrates, in a small way, how the cleaning-up operation could work.

The drive system consists of a Twin Deep Blue 50 i, each with a Deep Blue 40 kWh lithium battery.

The unique mission of this unusual vessel is what drew attention: freeing seas and oceans from plastic waste. Initially, it seems like a mad scheme given the 86 million tonnes of plastic waste WWF estimates are already in the sea, with almost 13 million tonnes added each year. Yet this vessel demonstrates, in a small way, how the cleaning-up operation could work.

Circular Explorer, as the boat was christened, belongs to the environmental organisation One Earth – One Ocean and was designed at a boatyard in Lübeck, Germany. If you take a closer look at this boat, you realise it’s an exceptional kind of catamaran. At the bows, between the two hulls, a conveyor belt transports any plastic items, bits of fishing nets or wooden planks out of the water and into the boat, where the crew sort them into big bags. Any seaweed, crustaceans, mussels, or other sea creatures are returned to the water via a slide at the boat’s stern.

“This project is very special for us, and we are delighted to be playing our part in making the natural environment that bit cleaner,” says Gregor Papadopoulos, Torqeedo’s Senior Manager Retail Sales.

The Circular Explorer is powered by two 50 kW Deep Blue electric motors.

The 24 solar panels can be tilted towards the sun and ensure that the Torqeedo Deep Blue system has plenty of power to run the Circular Explorer. (Credit: One Earth – One Ocean)

The 24 solar panels installed on the 64 m2 roof are tiltable and follow the sun to generate the necessary power. The two Deep Blue 40 kWh lithium batteries on board the Circular Explorer are charged via shore power before the boat sets off. But if the sun’s shining, they return to harbour fully charged. At a speed of 4 knots, the solar power generated during the trip is almost identical to the amount consumed. In other words, the Circular Explorer is not only on a cleaning-up mission but is also clean herself.

Autonomous cleaning-up boats and floating recycling centres

This boat is the next major step in a project that began in 2008. Back then, Günther Bonin, an ambitious leisure yachtsman and IT manager, was sailing from Vancouver Island to San Diego when he spotted the crew of a containership throwing tons of waste into the Pacific – a sight he could not forget. Back home in Munich, he started researching marine pollution and was shocked to discover how little was being done to prevent it.

Bonin gave up his job in IT and founded One Earth – One Ocean to raise awareness of marine pollution, research the topic, and develop concrete ways of tackling the problem of plastic waste thrown overboard from ships or that flows into the sea from rivers from countries without properly functioning waste-disposal systems.

Plastic waste is a considerable threat to the marine ecosystem. Fish, birds, and other marine creatures devour the plastic, are injured by it, and die. Carpets of floating garbage prevent sunlight from reaching the depths and inhibit the growth of plankton and algae. A few years ago, research scientists from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation calculated that if pollution continues at this rate, the plastic in our seas and oceans could weigh more than all the fish living there by 2050.

“We’ve got to clean up the water. Otherwise, we’re sawing through the life branches we’re sitting on,” says Bonin. The vision of the organisation’s founder and its more than 40 employees is to build up a global marine litter collection system.

They’re dreaming of many thousands of litter collection vessels operating in all the world’s major estuaries and autonomous vessels on the open sea that locate litter by satellite, collect it, and take it away. The plastic waste is to be recycled at sea and pressed into huge bales on converted midsized containerships. In the future, these floating recycling centres should even be capable of converting plastic to oil.

As early as 2050, the weight of plastic waste could exceed the weight of all fish – the Circular Explorer collects and recycles plastic.

Anyone who thinks these are just charming fantasies should look at a feasibility study drawn up by scientists from the University of Kiel, who are currently working on a plan to construct such a recycling ship. Thirteen of the small litter collection boats are already in operation around the world, cleaning up the Nile in Egypt, Guanabara Bay in Brazil, and Sangkat River in Cambodia. One Earth – One Ocean is initially concentrating on rivers, estuaries, and coastlines in Africa, South America, and Asia, which are the heaviest contributors to ocean plastic pollution. But most of these litter collection boats have been powered by diesel motors. Cleaning up the environment and polluting it simultaneously is not ideal, so the organisation decided to switch to solar power.

Operating off Manila five days a week

After the launch in Hamburg and sea trials, the Circular Explorer was taken apart, packed into four containers, and shipped to the Philippines. The vessel is currently operating five days a week cleaning up the massive bay off the country’s capital.

Günther Bonin’s team is expanding, adding another 20 people, including seven local fishers directly affected by the pollution who have a vested interest in the clean up. “Our approach is always to work with the local population right from the start,” he adds. Besides the fishermen, research scientists and teachers will be raising awareness of his organisation’s concerns among school and university students. “Simply collecting litter won’t solve the problem,” Günther points out. “We’ve also got to work on ensuring new litter isn’t constantly ending up in the sea.”

Torqeedo’s Gregor Papadopoulos also hopes that Bonin’s vision of a global marine litter collection scheme will become a reality – for business reasons and because he is convinced it will make the world a better place. A win-win situation.