Nev Watkins paused for breath as he worked his way up the steep hill from the Bonnie Doon wharf at Coasters Retreat.

Coasters Retreat is a sheltered anchorage at Pittwater in Sydney. (Supplied: Michael Troy)

The 83-year-old Watkins wanted to see the place of legend one more time, including his old mate Dicko’s house where the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race was born shortly after the end of World War II. It was a story he feared would die with him and he wanted to set the record straight.

Coasters Retreat is a tiny community of barely 40, water-access-only houses opposite Palm Beach first settled in the 1790s as a sheltered anchorage for boats known as coasters to sail produce from the Hawkesbury to Sydney.

Watkins made it up the steep path to the weatherboard cottage tucked away in the bush as the memories of the wild days of old came flooding back.

The present owners of the house, John and Louise Brogan, said it was 20 years ago when Nev dropped in unexpectedly.

“We saw him poking around and he seemed very familiar with the house and the clearing next door,” John said.

“We offered some water and shade, as he introduced himself as a mate of the original owner Selwyn Dickinson, or Dicko, as he was better known.”

Where it all started … Selwyn Dickinson’s house at Coasters Retreat where the original Sydney Hobart rebel sailors met.(Supplied: Michael Troy)

Rebel sailing trio high on the hill

As John remembers, Watkins was keen to tell the stories from the 1940s of the rebel sailors that lived in the three houses built in a row, 25 metres up from the water.

“He felt history had been made here and while most of the characters had long ago passed away, he was keen to write down his memories and leave them with us.”

A few days later Watkins returned with some handwritten notes as to how Dicko and his mates — who included actor Chips Rafferty and marine artist Jack Earl — had made the Pittwater area home after the horrors of the war.

In his notes, Watkins described Dicko as a lovable rogue, a diamond trader from Victoria who kept his precious gems in velvet pouches he carried in his pocket.

Watkins described Dicko as “a wonderful and friendly personality who often sailed around Pittwater in his yacht, ‘Sea Rover’, a 28-foot gaff-rigged couta”.

Dicko’s wife, Joyce, would spend three days a week alone in the house, while Dicko worked from his flat in Kings Cross.

Nev Watkins wanted to share his recollections about the people and places that formed the genesis of the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race.(Supplied: Michael Troy)

There was no telephone or power and all supplies had to be carried up the steep hill.

During the war, recreational vessels in Sydney were commandeered and no racing was allowed.

In 1944, with the Japanese in retreat, the Coasters Retreat boys often headed out to sea under the guise that they were helping keep an eye out for Japanese submarines.

A Couta boat similar to Sea Rover sailing in Sydney. (Supplied: Sea Museum)

Peter Luke’s “Wayfarer” and Charlie Cooper’s “Asgard” were among those that volunteered for the surveillance duty.

Watkins said a “rebel” group of Broken Bay sailors from Coasters Retreat split from the Royal Prince Alfred Club and would unofficially race three Saturdays out of four, races that always ended at Dicko’s place.

Rafferty’s rules apply at Coasters

The rebel numbers began to swell with the famous actor Chips Rafferty listed by Watkins as a regular visitor to Dicko’s.

He had returned from service in Papua New Guinea and, like many sailors, was attracted to the relaxed cruising waters around Pittwater.

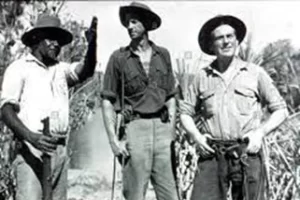

The knockabout lanky Australian actor was the rugged star of the classic movie, The Overlanders, a tale about the hardships of outback life that was considered way ahead of its time, with Indigenous actors in leading roles.

While filming The Overlanders, Rafferty was paid the huge sum — at the time — of 50 pounds a week, enabling him to buy a block of land at Lovett Bay with his wife, Quentin, in 1946.

Stockman Clyde Combo with star of The Overlanders, actor Chips Rafferty, centre, and director Harry Watt on location. Rafferty became one of the regulars at Coasters Retreat.(Supplied)

Quentin Rafferty with her actor husband, Chips, at Lovett Bay.(Supplied)

Rafferty loved time out from the spotlight and is said to have never made a trip across the bay without a crate of beer on board. He used the bottles to build a retaining wall with his policy that “drinking them on the site was part of the work scheme”.

Around the same time, two more intriguing figures joined the Coasters rebels, Norwegian shipping broker Sverre Berg and mining engineer John MacDiarmid Royle.

Royle was also in the movies, but not as an actor like Chips. It wasn’t till after his death that his story was immortalised in the movie Beneath Hill 60 (2010).

During World War I, Royle and fellow engineers were recruited as untrained soldiers to dig a series of tunnels underneath a German bunker and detonate the biggest bomb of the time.

The explosion destroyed part of the German front line and was acknowledged as a remarkable achievement.

His house’s present-day owners, Warwick and Wilma, said Royle dropped in many years ago.

John Royle’s former house at Coasters Retreat came with a Hill 60 reminder.(Supplied: Michael Troy)

Sailor and mining engineer John McDiarmid Royle with an electrical switch used to detonate explosives under Hill 60 at the Battle of Messines Ridge. (Supplied: Australian War Memorial)

“He was quite old but told us about his yacht and the water-collection system he made in the hills,” Warwick said.

While Royle lived at Coasters in the late 1960s, he met a German geophysicist, Willi Stackler, in Australia and the two discovered they had been in the same sector of the Western Front during the war.

It turns out that, while Royle was tunnelling, Stackler was “listening” for the vibrations with a primitive mobile seismograph or similar device.

Their mutual discovery is said to have resulted in much back-slapping and good-natured banter.

Berg finds Coasters a retreat from war

In between the two houses, another couple Sverre Berg and his wife, Tui, constructed a unique boomerang-shaped sandstone lodge in 1947, after escaping the horrors of war.

Berg had a fascinating journey to Australia, having left Norway in 1913 to get experience in shipping offices in Glasgow just before World War I broke out.

He ended up in Hong Kong, where he spent 24 years.

Business and official duties as the Norwegian consul brought him into contact with warlords, communist revolutionaries and Japanese officials.

Sverre and Tui Berg set up a new, post-war home at Coaster’s Retreat, where they would become part of the sailing community.(Supplied: Michael Troy)

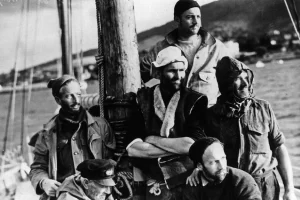

Former prisoner of war Sverre Berg, left, was one of the original Sydney Hobart sailors on his ketch, Horizon.(Supplied: CYCA Archives)

He witnessed the rise of Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek and their endeavours to unify China.

His halcyon days all ended abruptly, on Christmas Day on 1941, when — as a member of the Royal Hong Kong Volunteers — he was wounded while defending a six-inch gun at Fort Stanley and taken prisoner.

He spent years in the notorious Changi prison and worked on the infamous Burma railway.

The couple somehow found their way to Coasters Retreat where he was able to indulge his love of boating and bought the 40-foot ketch “Horizon”.

Bernard Stewart is the current owner of “Stone lodge”. He says his father, Les Stewart, had told him the story of the early Hobart legends.

“The three neighbours in the 1940s all had yachts they raced off the entrance to Broken Bay,” Bernard recalls.

“Sverre Berg’s Horizon was a larger ketch, and he was continually losing, although he was confident his skill and the boat would be evident over a longer distance.”

“After each loss, the frustrated ship broker would challenge the other two to a race to Hobart for a dozen bottles of beer.”

It’s probably no coincidence that part of the prize for a winner in the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race still includes “a dozen bottles of beer”, while the main meeting venue within the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA) building on New Beach Road is the Coasters Retreat room.

Berg went on to be commodore of the club and was acknowledged in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1953 as a formidable yachtsman.

“Horizon is owned and skippered by Sverre Berg, commodore of the CYC. He’s more than a first-class seaman. He’s a very tough skipper who’s sailed all over the world,” a story in the paper reads.

According to Watkins, in early 1944 the rogue sailors sent out an invitation to all yachts in the bay to take part in “The Dicko Cup”.

The entry fee was one bottle per boat and the prize: a polished IXL jam tin mounted on a wooden base.

Everyone headed back to Dicko’s cabin, the entrance bottles and more were quickly consumed but Watkins could not remember who won.

His note states simply that Harry Lloyd blew his bugle at midnight … a lot.

The rogues went on to form the Cruising Yacht Club and organised their first “cruise” from Manly in Sydney to Coasters in Pittwater on the October long weekend in 1944.

The Kathleen Gillett — named after the wife of boat owner Jack Earl — was one of the boats that ran in the first-ever Sydney Hobart Yacht Race in 1945.(Supplied: Cruising Yacht Club of Australia)

Watkins noted that Coasters was packed with anchored yachts and the party at Dicko’s went on for some time. The Dicko’s tin can cup was upgraded to the Founders Cup and won by Trygve Halvorsen’s yacht, Enterprise.

The yachtsmen were keen to venture a little further — 630 nautical miles further it turned out when several Tasmanians convinced them to go all the way to Hobart.

As yachting history officially records, in May 1945, Peter Luke, Jack Earl and Bert Walker invited prominent English sailor Captain John Illingworth RN to speak at a dinner in Sydney, where he famously suggested to “make a race” out of the proposed cruise to Hobart … and the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race was born.

Coasters Retreat, it turns out, is the true home of the CYC, although residents today are happy to be out of the spotlight and live quietly in the bush while cruising yachties pack the sheltered bay every weekend.

As to the characters of old … Watkins admitted some were difficult hard men to sail with but said the “Dicko’s cup rebels” were very gregarious and generous people who shouldn’t be overlooked for their part in creating one of the world’s great blue water classic races.

Michael Troy is a freelance journalist, sailor, guest speaker and raconteur. Apart from his superior skills in the media, he is also an expert in International Politics specialising in the Middle East, having graduated with a High Distinction in both subjects.

As a guest speaker, he will enthral you speaking about Epigenetics, the microbiome and dysbiotic drift. He says, “Science that I love to explain while sailing as the sea is the place ‘from whence we came’. However, I have catered for landlubbers with a simulated voyage through space and time to reach Elysia, the legendary resting place of worthy mortals”.

Michael Troy will be known to many, as a Senior Reporter / Producer for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

You can connect with Michael through LinkedIn.